We can now reconstruct the common phase in quantum field simulators!

Wave is one of the most fundamental phenomena in nature. Any wave has a “phase” which tells you where in the cycle the wave is at any given moment - think of a child’s swing or the rhythm of a dancer. At normal temperatures, the atoms inside a gas behave like particles, moving really fast and colliding with each other. But something wonderful happens if you cool the gas down to extremely low temperatures; they behave collectively as a wave. Such ultracold gases are said to behave as a “superfluid”. Unlike normal fluid, whose movement depends on external forces such as changes in pressure and temperature, the superfluid’s movement is dictated by the gradient of its “quantum phase”. Think of the quantum phase as an invisible terrain of valleys and hills, and the superfluid as a ball rolling in this terrain. When the slope is steeper, the superfluid moves faster. If you have two such superfluids, their phase difference tells you about their relative motion, while the sum of the phases is related to their common motion. A bulk of previous theoretical and experimental work focuses on extracting and studying phase differences between two superfluids, while the total phase (or the “common” phase) is often ignored.

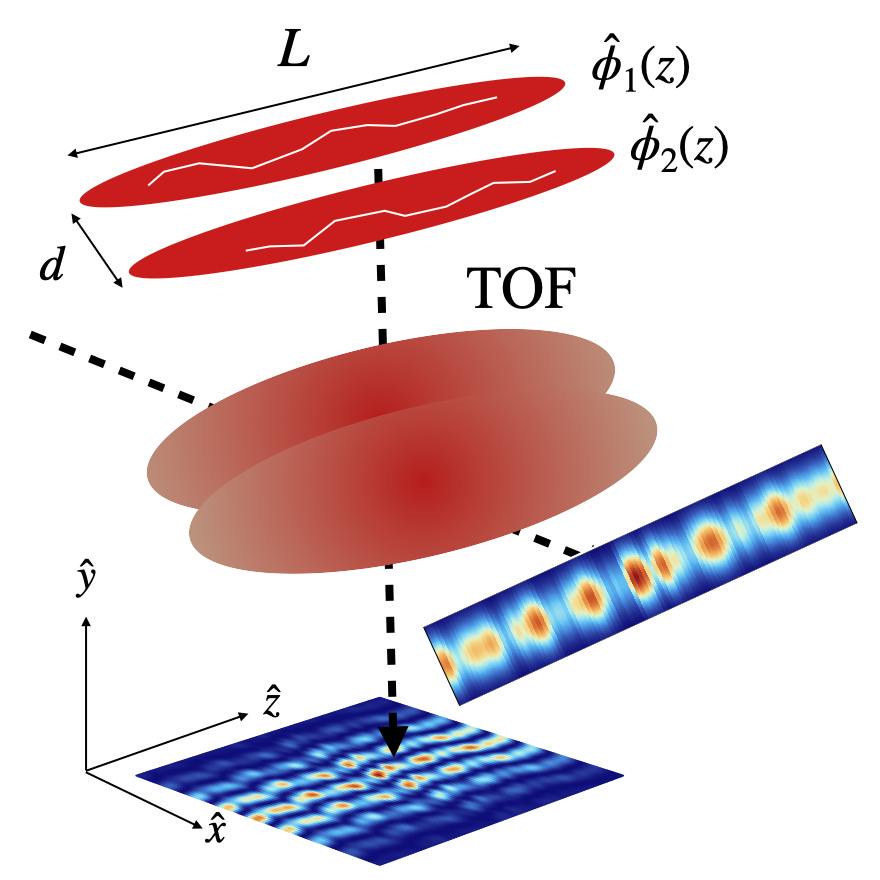

In this work, we show that we can extract information about the total phase of two or more superfluids in experiments by inverting the continuity equation, i.e. by observing its motion. We support this with theoretical analysis, numerical simulation, and experimental demonstration using one-dimensional superfluids realised in the TU Wien Atomchip group. Why is this important? The total phase information is crucial for studying long-time thermalization and entanglement between the two superfluids. But that’s a story for another day ;) Read more about this in our latest publication at PRR!

Written by: Taufiq Murtadho